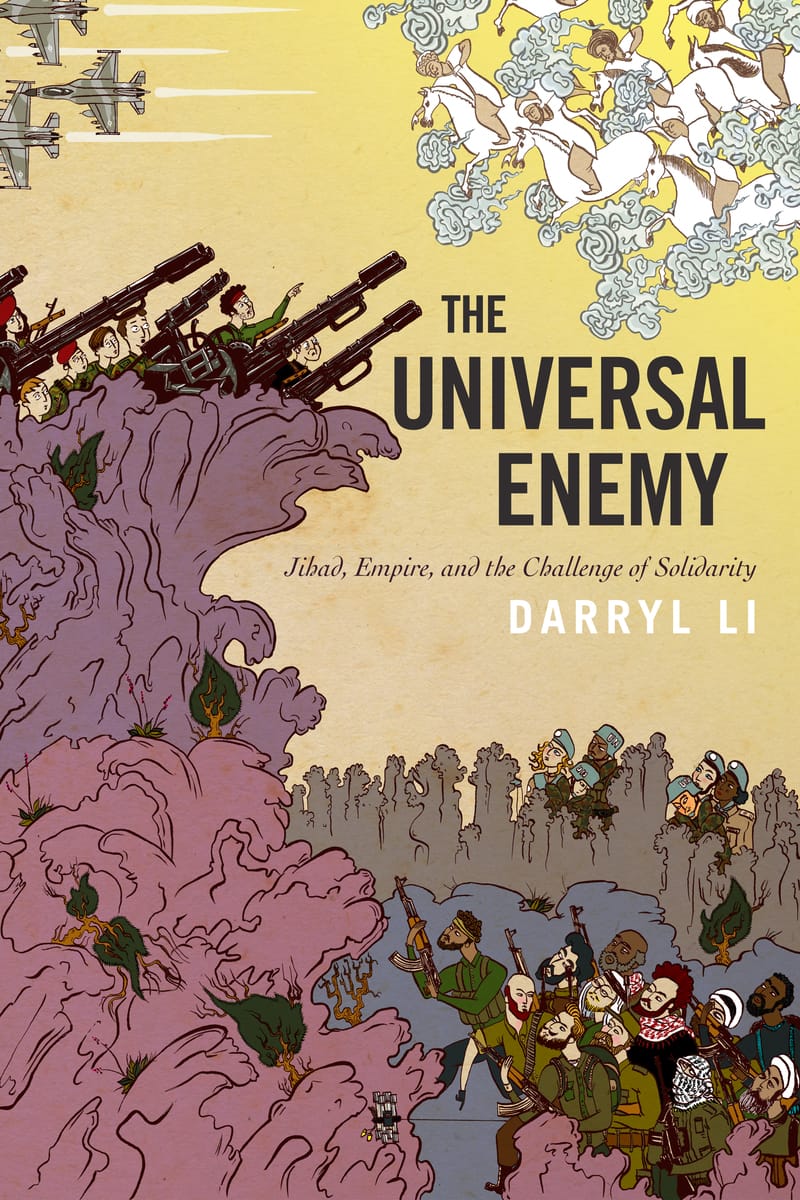

Solidarity Is a Country Far Away

Anna Simone Reumert reviews Darryl Li's book The Universal Enemy: Jihad, Empire and the Challenge of Solidarity, an eye-opening ethnographic history of the experience and fate of foreign fighters acting in the name of global Muslim solidarity in the Bosnian war of the 1990s.