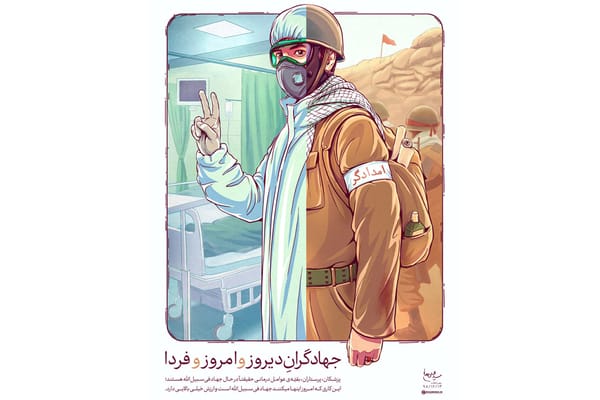

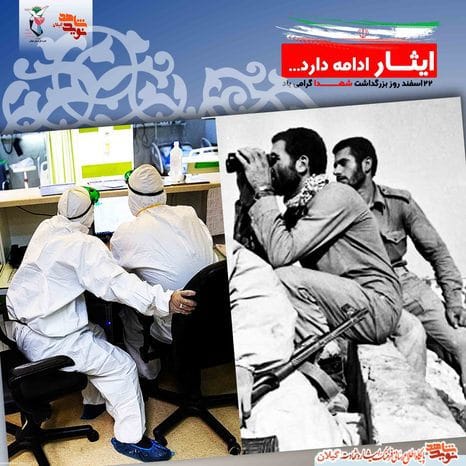

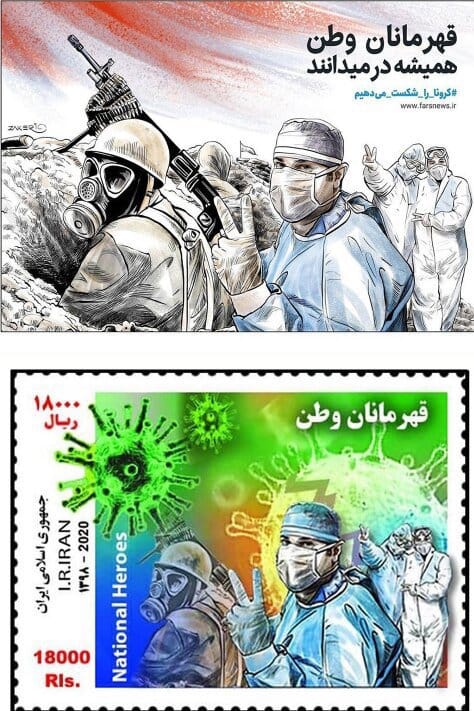

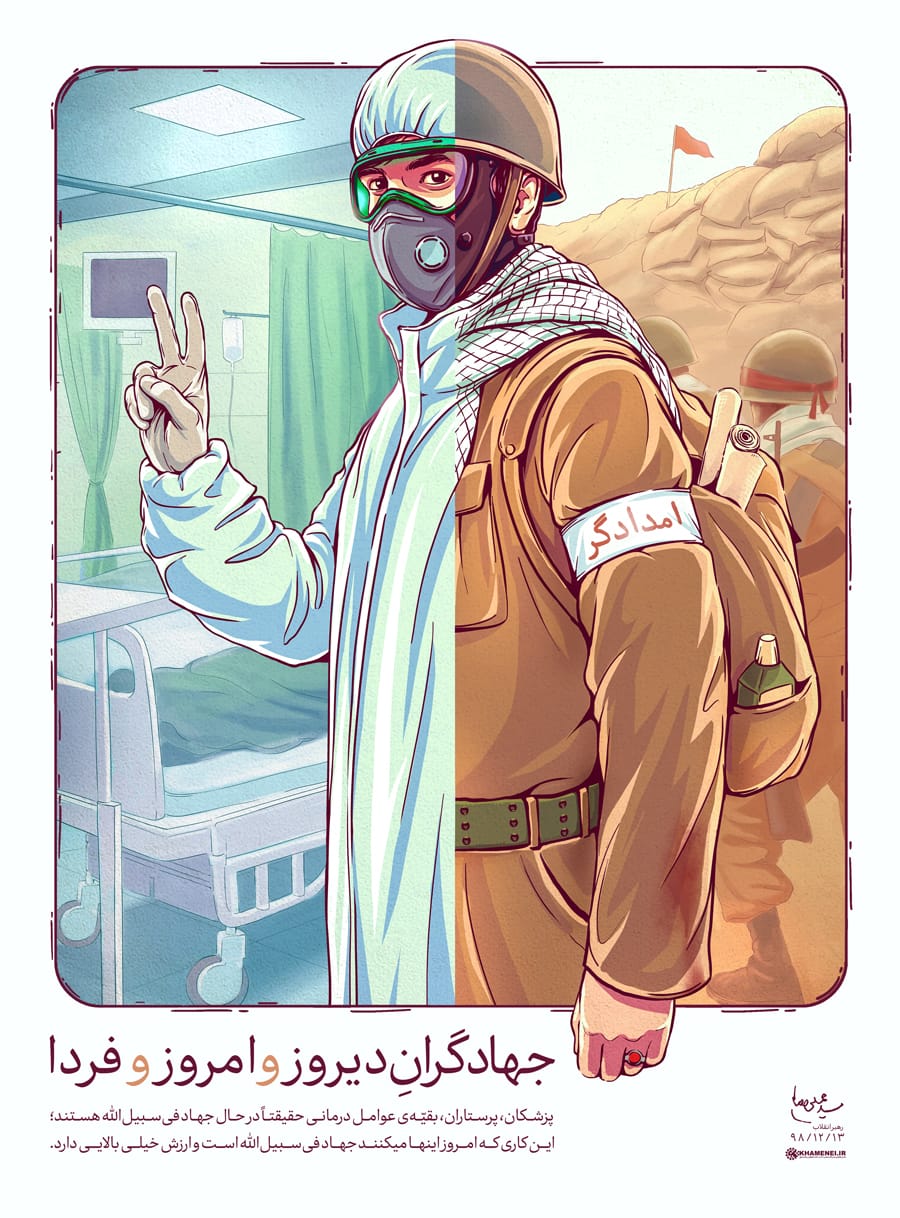

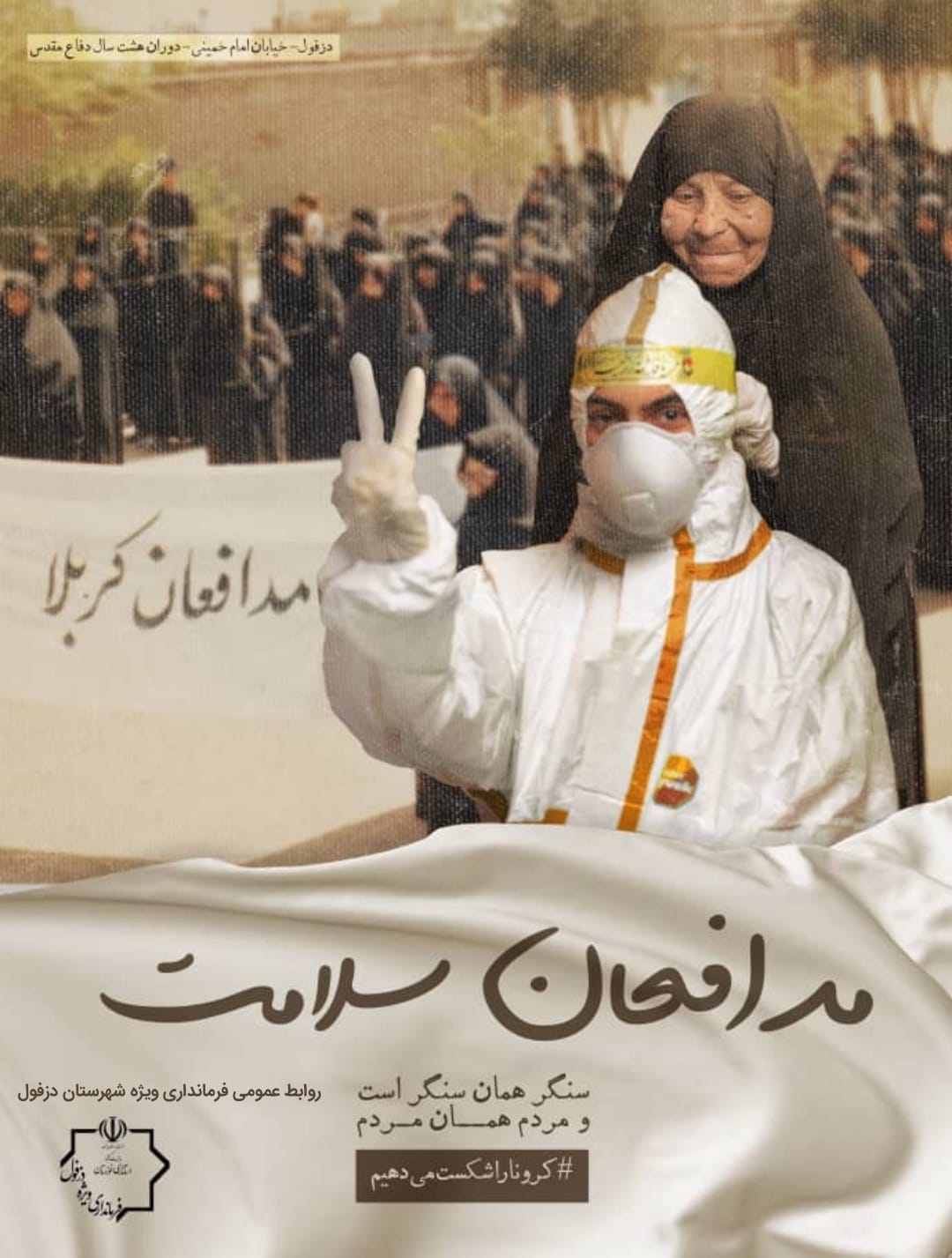

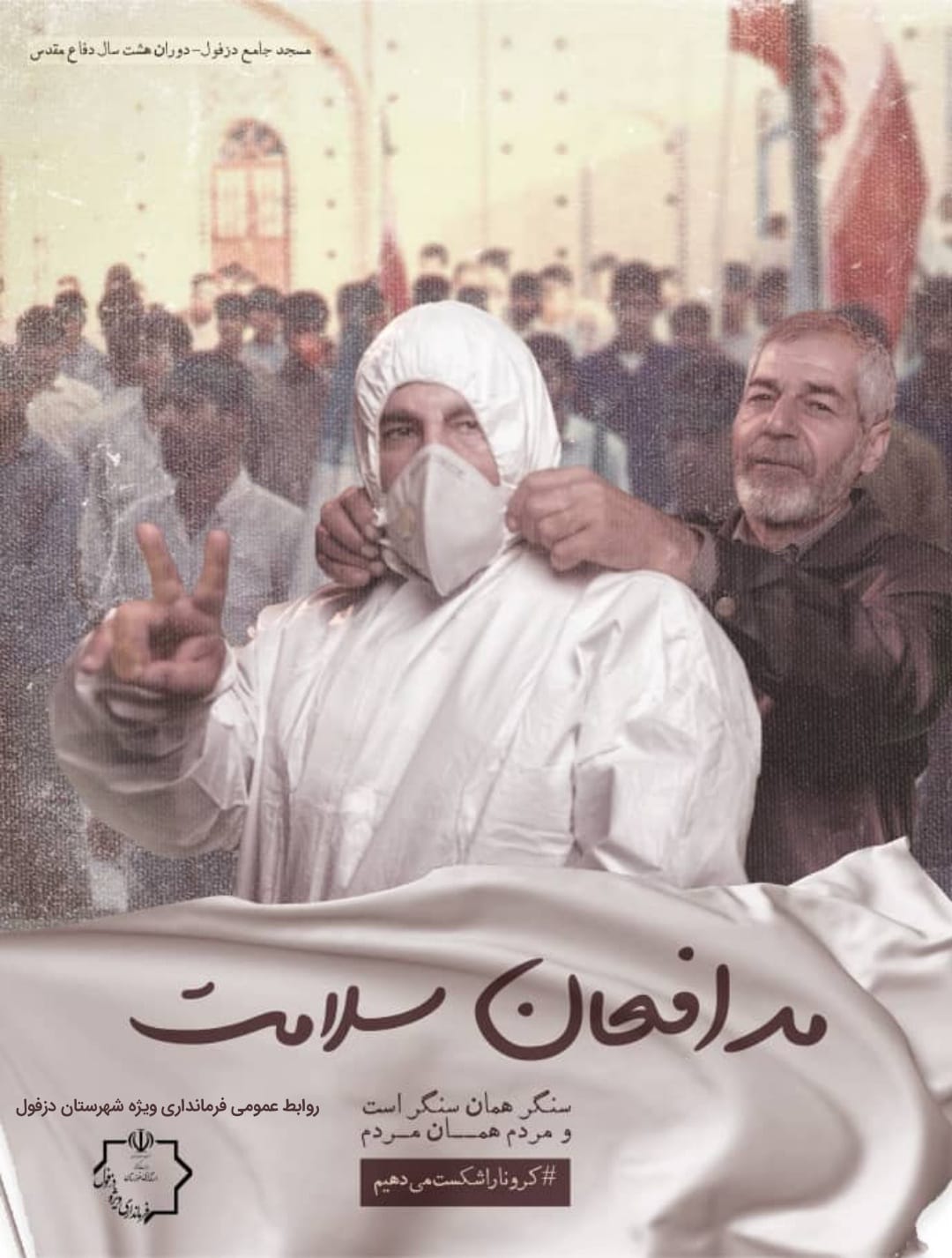

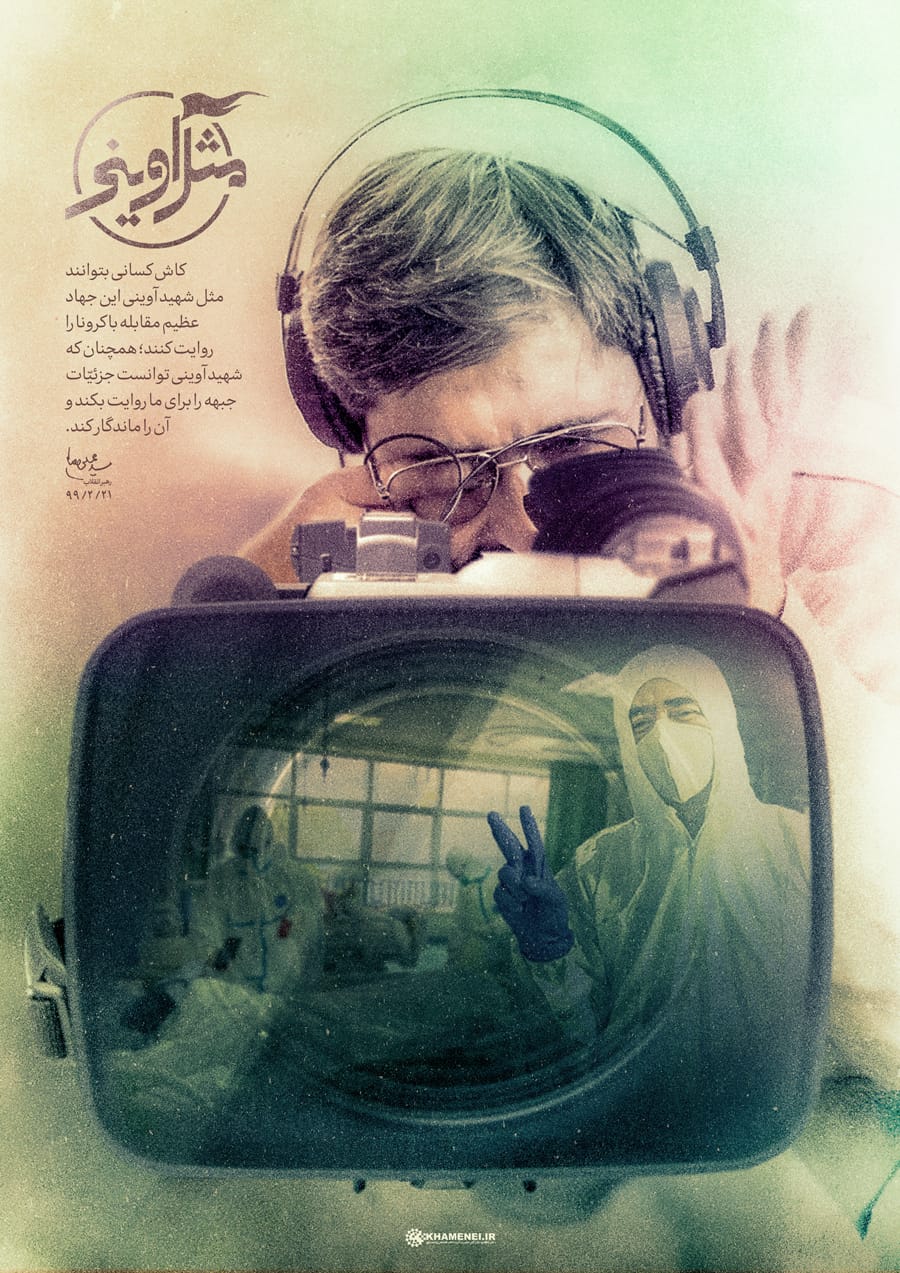

Going to War with the Coronavirus and Maintaining the State of Resistance in Iran

The Iranian government is fighting against the coronavirus pandemic not only with travel restrictions and social distancing rules, but also with ideological tools that promote unity and resistance. Through the production of posters and other media, Iran is creating connections between earlier battle