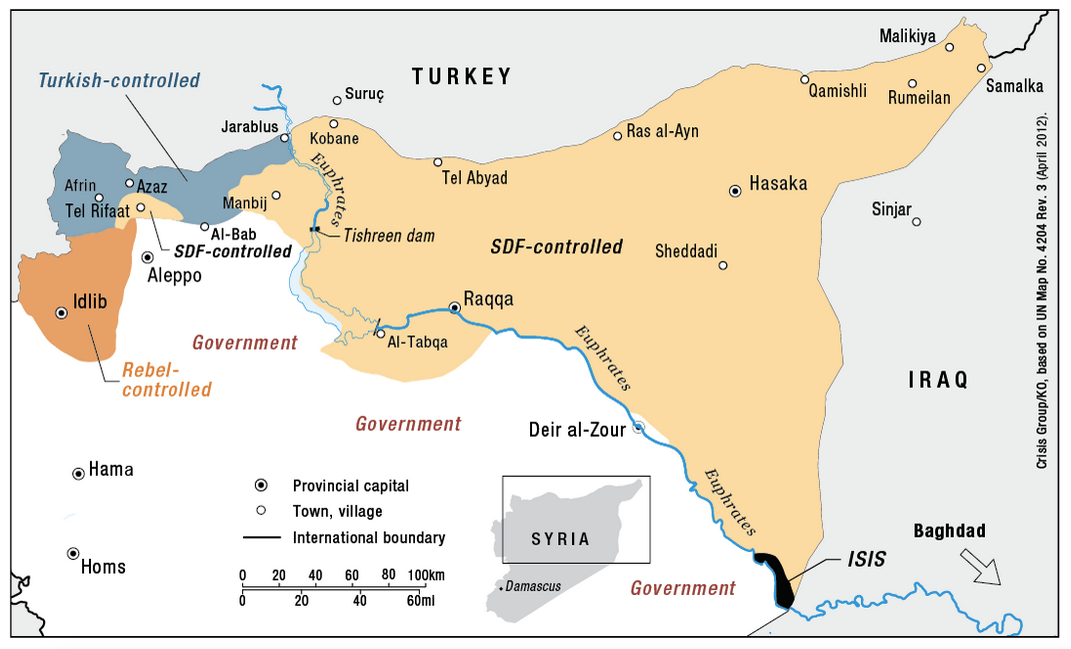

Arabs Across Syria Join the Kurdish-Led Syrian Democratic Forces

The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) defending it were established by Kurdish political and military forces. But the SDF also attracts recruits from all over Syria. Why do Arabs from areas both inside and outside SDF control join this military