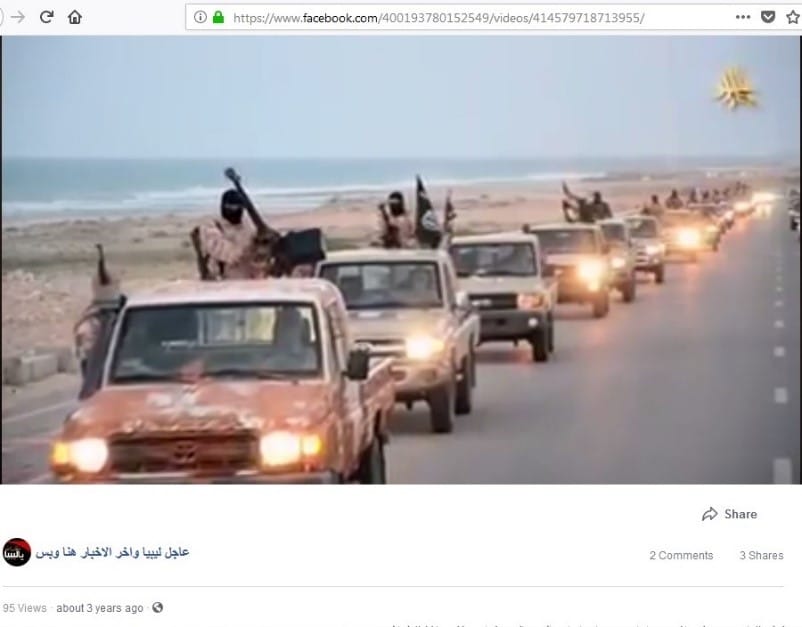

Russia Opens Digital Interference Front in Libya

The Middle East is increasingly awash with fake news and misinformation campaigns. Russia has become a major vector of these disinformation campaigns, affecting virtually every major flashpoint in the Arab world. It just opened a new info-war front in Libya.