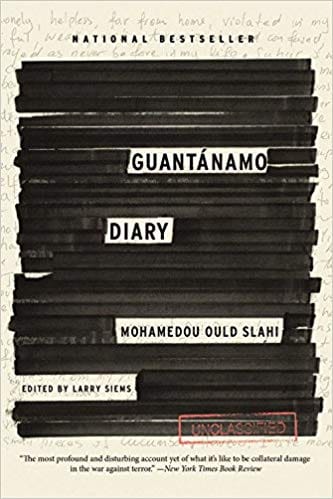

Slahi, Guantanamo Diary

Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s Guantánamo Diary is a powerful indictment of the cruel regime of torture at the heart of darkness that is the prison camp at Guantánamo Bay.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi, Guantánamo Diary (New York: Little, Brown, 2015).

Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s Guantánamo Diary is at least the fifth autobiography by a Guantánamo prisoner. But because Slahi remains in US custody, unlike the others, his is the only first-person account that the government had the power to redact. Indeed, Guantánamo Diary can be read as two intersecting narratives. One story is Slahi’s own—the recollections and reflections on his experiences as a wanted, captured, disappeared, tortured, broken, yet unwaveringly devout and highly intelligent man. The other story, conveyed through heavy redactions that block words and passages throughout the book—including the entirety of one of Slahi’s poems and female gender pronouns when he describes his interrogators—is a grim and embarrassing account of the state of US intelligence work in the “war on terror.” The book’s editor, Larry Siems, uses footnotes to fill in some of the information blocked out by redactions but available in the public domain, including several official investigations into the Bush administration’s regime of torture.

Slahi’s journey to the dark side begins in his native Mauritania, where his government, for no reason other than to curry favor with the United States, takes him into custody in November 2001 and agrees to his rendition to Jordan, where he is imprisoned for seven and a half months. Between 2001 and 2004, Slahi was one of at least 13 people sent to Jordan for interrogation and torture at the behest of the Americans. The Canadian government is also implicated because Slahi lived in Canada for a brief while, and the Canadians provide threads from some of Slahi’s innocuous phone conversations, for example the mention of “tea and sugar” that American intelligence agents begin to spin, like delusional Rumpelstiltskins, into the whole cloth of a terrorist plot. In July 2002, the CIA renders Slahi from Jordan to the Bagram prison in Afghanistan, and then on August 4, transports him to Guantánamo.

Slahi was ranked the top terrorist at Guantánamo, not on the basis of any evidence of wrongdoing but rather because his life raised questions that lacked answers—at least ones the government was willing to believe. Initially, he was questioned about and then deemed presumptively guilty of involvement in the so-called Millennium Plot to bomb the Los Angeles airport. Why? Somewhere along the line he and Ahmed Ressam, who was convicted for the plot, crossed paths. Ressam never implicated Slahi, however. The Millennium Plot was small potatoes. Slahi would soon rise up the “mosaic theory” path to the pinnacle of official suspicion as the person who recruited Ramzi bin al-Shibh for the September 11 attacks. This suspicion can be gleaned, despite all the redactions, through Slahi’s account of the trajectory of his questioning and treatment.

Slahi was subjected to some of the worst torture on offer at Guantánamo with the full knowledge and facilitation of the US government. The paper trail includes a memo signed by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld on December 22, 2002, authorizing a menu of harsh techniques; a memo signed by John Yoo in the Office of Legal Counsel, dated March 13, 2003, to squelch opposition by top military lawyers and which reprised the reasoning in Yoo’s August 1, 2002 memo to the CIA; and a policy directive signed by Rumsfeld on April 16, 2003, which was the prelude to the “special interrogation plan” for Slahi. Thus, with chain-of-command authorization and a legal “golden shield,” the torment intensified.

Slahi’s autobiography fills in the well-known story about how military interrogators sought and received permission to torture prisoners at Guantánamo. Two of Slahi’s personal “vulnerabilities” that were exploited by his interrogators were his love for his family and his religious devotion, which includes modesty. He was stripped and sexually molested by female interrogators. His interrogators threatened rape against his wife, his mother and him, and not just any rape but “American rape,” which has come to occupy a hyper-scary place in the pantheon of rape cultures. He recounts the words of one interrogator: “In American jails, terrorists like you get raped by multiple men at the same time…. [B]eing raped is inevitable.”

Around June 18, 2003, Slahi was moved to the India Block in Camp Echo where he was held in absolute isolation. He was barred from praying and punished if he was caught doing so, and he was denied all “comfort items” including toilet paper and soap. He writes: “I was living literally in terror. For the next seventy days, I wouldn’t know the sweetness of sleeping: interrogations 24 hours a day, three and sometimes four shifts a day.” His breaking point was the infamous “boat ride,” which started with a vicious beating and involved several hours of being sailed about with the intention of making him think he was being taken to a far more horrible place. Two men posing as foreign interrogators, one Egyptian and one Jordanian, were part of the violent charade.

Slahi describes this traumatic seaborne episode as “a milestone in my interrogation history…. A thick line was drawn between my past and my future with the first hit [REDACTED] delivered to me.” His words and sentiments echo those of Jean Amery, a Belgian Jew who was tortured by the Nazis before being sent to a concentration camp: “The first blow brings home to the prisoner that he is helpless” and he loses “trust in the world.” And “[w]hoever was tortured, stays tortured.” Slahi, resigned finally to his helplessness, decided to tell the interrogators what they wanted to hear to make the torment stop. He produced a string of wild stories that drew on the lines of his years-long questioning, including a plot to blow up the CN tower in Toronto (a structure he had never heard of before being imprisoned), and that he was a top al-Qaeda recruiter. Then he signed the statement, and that made it “true.” Since then, Slahi has been imprisoned in a special facility within the prison where he is treated like someone in a witness protection program.

In 2010, the judge who heard Slahi’s habeas corpus petition ordered his release. But the Obama administration appealed, and the DC Circuit Court of Appeals sent his case back to the district court for a rehearing, where it is still pending. The unredacted manuscript remains classified.