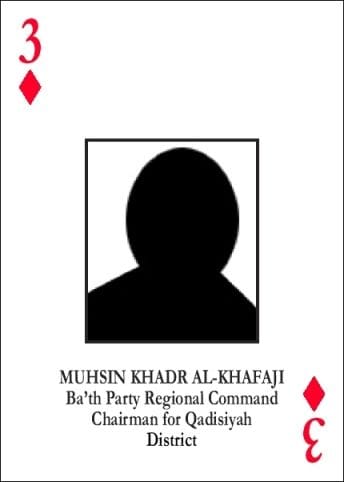

Looking for the Three of Diamonds

A few years ago, I began work on a crime novel set in Iraq [http://www.bitterlemonpress.com/new-books/american-crime-fiction/baghdad-central.asp]. I borrowed the name of a real-life person, Muhsin Khadr al-Khafaji, as a writing prompt. Taking this man’s name seemed like nothing since my character wa